The Revolution Dome

Michael Passmore

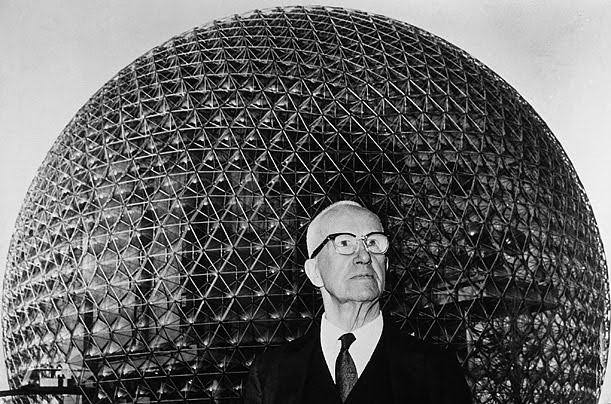

When Michael was first approached to build something for the 2017 symposium, his first idea was a pizza oven in the college grounds. However, he decided there was already an abundance of food already available so he opted to build a geodesic dome instead. Michael’s interest in domes can be traced back to his study of Buckminster Fuller. Fuller was a true renaissance man; architect, poet, engineer and author, his sister described him as a “veritable ideas factory”. Merce Cunningham worked with him at Washington University. Reminiscing about this time, Cunningham said, “It was Bucky Fuller and his magic show. He was like the Wizard of Oz but with all the gadgets working”.

The US government faced a severe housing crisis after the Second World War. Fuller believed his geodesic domes could solve it owing to the efficiency of their shape and their ability to be constructed rapidly using inexpensive materials. The domes were going to be built in the aircraft factories that became defunct after 1945. But despite his initial enthusiasm, Fuller was not happy with the design and wanted more time to work on it. His stockbrokers and the government, however, were keen to press ahead with the project and pressured him into signing it off. Other problems arose from the construction trade unions who refused to work on the houses because they already came equipped with plumbing and electricity and therefore risking many people’s jobs. The banks were unwilling to finance the project with the risk of union disruption and stockbroker dissatisfaction, leading Fuller to pull the project entirely. Consequently, only one of these domes was built; it is still standing in Montreal today. Fuller’s more successful project was the Union Tank dome in Baton Rouge that at three hundred and eighty four feet held the title of the largest span structure in the world.

Michael was attracted to images of homemade domes made from bits of old building and covered with car panels. This was popularised in the 1960s by artists who set up the Drop City community in Colorado. Inspired by Fuller and other figures from Black Mountain College, they built domes for domestic habitation from old car bonnets. Michael was particularly drawn to their patchwork aesthetic. In terms of architectural design, Michael turned to a man called Paul Robinson, who has pioneered a method of geodesic dome construction by developing Fuller’s earlier work. The beaver edge frame system is a method for constructing greenhouses using triangles. The finished structure can be covered with any material.

Most domes are based on an icosahedron, a twenty-sided solid made of twenty triangles. Five are at the top, five are at the bottom, and ten are round the middle. For the revolution dome, Michael divided each large triangle into four, thereby creating sixteen triangles in each big triangle. He calls this a four-frequency dome. The geometry of the dome generated six different types of triangle. At the centre of each large triangle is an equilateral triangle made out of polythene, which is surrounded by one isosceles triangle. The others are scalene triangles and are mirror images of each other. The curvature comes out of from the geometry of the six different triangles and the struts, which form the frame members, are all bedevilled towards the centre of the sphere.

The dome was built in one week with students from various programmes, including Scenic Arts, ETA and Lighting Design. The level of commitment required and sense of secrecy surrounding the project created a great deal of excitement and anticipation in the student body. It has already been used as a bar since its completion. Staff are now considering how it might be used as a performance and events space. The relatively low cost of the materials begs the question as to how larger temporary structures could free up rehearsal spaces and diversify the types of productions the college programmes.

Maximising the Site, Maximising Potential

In her capacity as director of the annual symposium, Professor Nesta Jones instructs the designers to think of the college grounds as a text to be activated by lighting, sound and objects. This is distinct from treating site as a space to stage plays – the material is the site. Unfortunately, the symposium is one of the very few occasions when the college lawns are used in this way, despite the fact that the grounds are replete with potential arenas for installations and immersive performances. Constructing temporary spaces like the revolution dome are one way to maximise the college’s resources. The precision of the dome’s design is an excellent example of applied mathematics and science, meaning it has great potential as an outreach activity with schools and colleges. The students’ sense of accomplishment after building the dome was palpable; being part of the team was a badge of honour. Building temporary structures could also be a way to plant seeds of ambition in children and young people who will be able to see how the sciences work in the performing arts.

Practice, Reflect, Share

Professor Paul Fryer, in partnership with Professor Paul Allain (University of Kent) and David Shirley (University of Manchester), hosted the Practice, Reflect, Share event to discuss how to produce research and to explore research’s relationship to practice. Attendees included academics from Royal Holloway, CSSD, the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, GSA, and The Arts University, Bournemouth. The journals and publication outlets represented included Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, Digital Theatre +, The Journal of Embodied Research, and Theatre and Performance Design.

Professor Paul Fryer, in partnership with Professor Paul Allain (University of Kent) and David Shirley (University of Manchester), hosted the Practice, Reflect, Share event to discuss how to produce research and to explore research’s relationship to practice. Attendees included academics from Royal Holloway, CSSD, the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, GSA, and The Arts University, Bournemouth. The journals and publication outlets represented included Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, Digital Theatre +, The Journal of Embodied Research, and Theatre and Performance Design.

The impetus for hosting Practice, Reflect, Share at Rose Bruford comes from a recognition that the research culture in UK HEIs is undergoing significant changes. Taken together, the REF, the increasing student demands on resources and contact time, technological innovations, and the as yet unknown impact of Brexit on government funding formulas, compel academics to reappraise the ways practice, teaching and research activities can co-exist and, indeed, enhance each other. The definition of “practice research” will remain ongoing, fuelled as it is by innovative methodologies and diversifying outcomes of projects. However, it is important that we try to articulate some common understanding of the term in order for genuine knowledge exchange to take place.

The program for the day included a keynote presentation by Miguel Mera, a plenary, and round table discussions on the subjects of mentoring, networking and publishing, collaborating, and practice and research. Issues pertaining to documentation of process and dissemination of outputs was a subject that came up consistently. There was a general recognition that the internet create many exciting new avenues of public engagement but a culture shift needs to occur if it is to be fully utilised. Specifically, the authority of written text acts a barrier to experimenting with the visual formats of video and photography as a means of positing a theory or citing evidence of process. A related issue concerns the publics to which research targets and reaches. Open access online publication platforms are a potential way of increasing the impact of one’s research, but there are risks involved. The inability to oversee the transmission of the knowledge one has generated can lead to its distillation. Moreover, it is worth asking what the other functions dissemination can fulfil beyond impact. Ben Spatz opined that an awareness of the publics a piece of research is intended for can enable academics to build constituencies and communities.

The program for the day included a keynote presentation by Miguel Mera, a plenary, and round table discussions on the subjects of mentoring, networking and publishing, collaborating, and practice and research. Issues pertaining to documentation of process and dissemination of outputs was a subject that came up consistently. There was a general recognition that the internet create many exciting new avenues of public engagement but a culture shift needs to occur if it is to be fully utilised. Specifically, the authority of written text acts a barrier to experimenting with the visual formats of video and photography as a means of positing a theory or citing evidence of process. A related issue concerns the publics to which research targets and reaches. Open access online publication platforms are a potential way of increasing the impact of one’s research, but there are risks involved. The inability to oversee the transmission of the knowledge one has generated can lead to its distillation. Moreover, it is worth asking what the other functions dissemination can fulfil beyond impact. Ben Spatz opined that an awareness of the publics a piece of research is intended for can enable academics to build constituencies and communities.  This approach certainly increases the likelihood of research being a catalyst for collaborations between different disciplines. It was also mentioned that dissemination can be expressed as a form of inviting people into an ongoing process into knowledge production. The public, in this context, have a reciprocal relationship with an author’s developing corpus. A page on Theatre Futures has been set up for delegates to share information.

This approach certainly increases the likelihood of research being a catalyst for collaborations between different disciplines. It was also mentioned that dissemination can be expressed as a form of inviting people into an ongoing process into knowledge production. The public, in this context, have a reciprocal relationship with an author’s developing corpus. A page on Theatre Futures has been set up for delegates to share information.

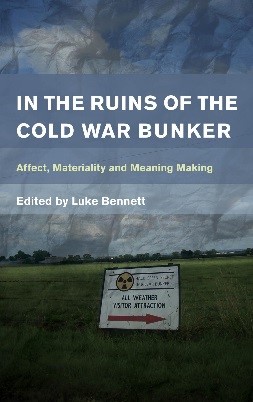

New Publication on Bunkers

Kathy Sandys

Kathy’s chapter ‘Sublime Concrete: The fantasy bunker, explored’ has been published by Rowan and Littlefield in In The Ruins of the Cold War Bunker: Affect, Materiality and Meaning Making. The blurb of the book reads:

During the Cold War military and civil defence bunkers were an evocative materialisation of deadly military stand-off. They were also a symbol of a deeply affective, pervasive anxiety about the prospect of world-destroying nuclear war. But following the sudden fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 these sites were swiftly abandoned, and exposed to both material and semantic ruination.This volume investigates the uses and meanings now projected onto these seeming blank, derelict spaces. It explores how engagements with bunker ruins provide fertile ground for the study of improvised meaning making, place-attachment, hobby practices, social materiality and trauma studies. With its commentators ranging across the arts and humanities and the social sciences, this multi-disciplinary collection sets a concern with the phenomenological qualities of these places as contemporary ruins – and of their strange affective affordances – alongside scholarship examining how these places embody, and/or otherwise connect with their Cold War originations and purpose both materially and through memory and trauma. Each contribution reflexively considers the process of engaging with these places – and whether via the archive or direct sensory immersion. In doing so the book broadens the bunker’s contemporary signification and contributes to theoretically informed analysis of ruination, place attachment, meaning making, and material culture.

Kathy explores the aesthetic properties of the bunker and their evocations of factual and fictional memories of the Cold War. She argues meaning emerges from these places through engagement with their spatial and material properties. The chapter contextualises this analysis with reference to Kathy’s installation work.